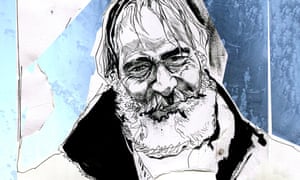

Hamid Farahi Alamdari was full of stories. When he was living out of his car in a Tesco car park in Harlow, Essex, he told anyone who would listen about his exciting past as an avionics engineer, Iranian war veteran and physicist. Then there was his pièce de résistance: the time he was shortlisted to be Stephen Hawking’s assistant. “I took it all with a pinch of salt at first because he was telling me all these stories and I could tell he was a drinker,” says account manager Adam Protheroe. “He could have been anybody. He could have told me that he was the king of Iran and I wouldn’t have known any better.”

Protheroe became close friends with Hamid in 2017. “I’d seen him around and he was living in a Peugeot 206 that was parked up just around the corner. I came back a couple of days later with a bag full of clothes and bits and pieces and socks. My wife cooked him a nice meal and I took it down to him in a little box and started talking to him from there.”

He would eat with him, take him to appointments and raised more than £700 to get Hamid accommodation in the winter that followed. Protheroe wasn’t bothered whether he was telling the truth or not. He liked Hamid, and who wouldn’t spin a yarn or two when life had dealt them such a bum deal?

Protheroe was by no means the only one to fall for Hamid’s raffish charm. Many of the locals had a soft spot for the bearded stranger with the laughter lines and exotic accent. Hamid chatted to his new friends about literature and science, spiritualism and martial arts, Iraq and war, pretty much anything. And then one day he was gone. Just as he had arrived unannounced, he disappeared. In February 2018, Hamid was taken ill and moved into emergency accommodation. He died there alone. Like two-thirds of homeless people, Hamid suffered with addiction. And like many people who die homeless, he looked far older than his 55 years.

Harlow is one of the new towns built after the second world war to ease overcrowding in London. In its early years it had a thoroughly modern can-do feel to it, boasting Britain’s first all-pedestrian shopping precinct and first modern high-rise residential tower block. But more recently it has fallen on tough times. This year, Harlow’s Conservative MP, Robert Halfon, suggested the town had become a dumping ground for London councils, which have sent hundreds of “troubled families” to live in converted office blocks in his constituency. The last census, in 2011, showed that Harlow had higher unemployment, less home ownership, lower educational qualifications and poorer health than the average for both Essex and England.

In June, however, Halfon said things were looking up for the town. “The news that homelessness is at its lowest level since 2010 is a real step in the right direction,” he declared. Halfon quoted the absurdly low figure of five homeless people, and was soon corrected by a local Labour councillor, Tony Edwards, who pointed out that the figure referred to rough sleeping not homelessness, and that in fact more than 4,500 people were on the housing-needs register in Harlow and about 400 people had made “homeless” applications in 2018/19. That paints a very different picture. It means that, with a population of 85,000, 5.3% of people in the town are waiting to have a housing need met.

It is 18 months since Hamid died, and we meet Protheroe in the Tesco superstore cafe where he and Hamid would often get together for coffee and bacon sandwiches. Protheroe is business-like and comes straight to the point. He says he doesn’t want us to get the wrong impression; he’s not a do-gooder. He considered Hamid a friend rather than a charity case. “I’m not a selfish bastard, but I’m not out to help everybody I can,” he says. “If anything, I’ll help animals more than I’ll help people. I just got to know Hamid and we became mates.”

Hamid told Protheroe he had ended up homeless in 2017 after selling his pension in a dodgy deal and then running into money troubles. But even here there is a mystery. Unlike most people living on the streets, he still had savings in the bank. He camped in woodland close to Tesco until his tent was set alight. Protheroe says Hamid told him that teenagers were responsible, but he didn’t like to talk about it.

Soon after this a Harlow local gave Hamid the old Peugeot 206. He parked it by Tesco and moved in. The interior of his car-home was crammed with donated clothes and books – science books, spiritual self-help guides, novels, all sorts. The only space left for Hamid was the passenger seat. Protheroe thought his friend might be an eccentric hoarder.

Hamid told Protheroe he had ended up homeless in 2017 after selling his pension in a dodgy deal and then running into money troubles. But even here there is a mystery. Unlike most people living on the streets, he still had savings in the bank. He camped in woodland close to Tesco until his tent was set alight. Protheroe says Hamid told him that teenagers were responsible, but he didn’t like to talk about it.

Soon after this a Harlow local gave Hamid the old Peugeot 206. He parked it by Tesco and moved in. The interior of his car-home was crammed with donated clothes and books – science books, spiritual self-help guides, novels, all sorts. The only space left for Hamid was the passenger seat. Protheroe thought his friend might be an eccentric hoarder.

Hamid told him he spoke seven languages, that he had a PhD in astrophysics and theoretical maths, and mentioned the job he almost got with the late Prof Hawking. He also talked about fighting in the Iran-Iraq war, showed him photographs of members of his platoon who had died, and told him he suffered from terrible flashbacks. That’s why he drank, he said – to blot out the memories. Protheroe is surprised by how well they got to know each other in such a short period of time. He would find himself visiting Hamid at night to make sure he was OK.

Although Hamid was a good deal older, 41-year-old Protheroe found himself playing a paternal role. He would often tick Hamid off about the state of his car-home. “I’d open up the car door and he’d been smoking roll-ups in there. I said you’ve got to sleep in there, and there’s smoke billowing out. It wasn’t the kind of car I would have liked to have slept in, if I’m being honest. Hamid wasn’t very tidy. I’d have a go at him – ‘Sort yourself out, you look like a sack of shit, you need to run a brush through your hair.’ I’d just have a dig at him and we’d have a bit of back and forth. He’d laugh at me, and take the piss.”

Like Protheroe, Chrissy Sorce is almost apologetic about befriending Hamid. “I don’t know why I took to him. I don’t go out and randomly do that to everybody. It’s just something about him – he was likable.” Sorce, who is 51, works at a car-rental firm based in the industrial park next to Tesco. “He parked the Peugeot behind our workplace, and I just started chatting to him on my fag breaks,” she recalls.

Sorce talks about his fondness for scratch cards – “He was always trying to win millions, bless him” – and how she stored books for him in her daughter’s shed to free up space in the Peugeot. “They were quite intellectual books. He was very educated. But something obviously went wrong somewhere along the line, which can happen, can’t it?”

Hamid told Sorce many fascinating and funny stories. But for all that, there was a terrible vulnerability about him, she says. “It was all a fake, really, because at the end of the day he was still lying in that car and sleeping in the freezing cold.” Sometimes when he was drunk he would weep and tell her he wished he was dead. Sorce says she told him not to be daft, and to take any opportunity that came along. But she admits, at this stage of his life, few opportunities were coming his way. “I think the council could have housed him. He could have been put in a room a lot sooner, surely. They all knew where he was.”

What she most liked about Hamid is that he didn’t want anything from her. “He never even asked me for a pound.” She pauses and smiles. “He did ask me to go out for dinner, though, but I had to let him down and say no. I think he liked the women. He would go into Tesco and chat to them.” She once did his washing for him, she says. “I washed and ironed everything. I said to him: ‘Do you want me to do any more?’ But he never gave me any more to do. He was proud. After I did that, he went out and bought me washing powder to replace what I’d done. I told him not to bother, but he did it anyway.”

She knows some people couldn’t understand why she wanted to help him. They said it straight out to her. “When I took home his washing – and yes, it really did stink – one of my managers said: ‘Eeeeugh, how could you wash all his clothes?’ I said: ‘Easy, you just put them in the washing machine and take them out.’” Sorce says she couldn’t help thinking it could just as easily have been her living in that car. “We’re all one pay cheque away from being homeless. You never know what’s going to bring you down, that’s how I see it.”

At times, she says, Hamid seemed confused. She and Protheroe believe he had early-stage dementia. As for his stories, she didn’t know what to make of them. “You never know what’s true and what’s not, do you? You just go along with it.”

To continue reading this fascinating article, click here: A gifted physicist

The Guardian

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario